A sand museum in the desert

Fourth experiment 12'48"

on the tenth day, he finds himself in a museum full of strange objects, musical instruments from impenetrable cultures. A worn sound has brought him there, it comes from a cylinder of a waxy material spinning in front of him in a strange machine, with each turn of the needle it releases sand. It covers his feet, it covers the entire floor of the museum. The sand shifts with each cycle of the cylinder, like a mechanical tide inexorably rising. Now he has more control over the technique of the experiment; he can move about the building and its rooms under the light that falls through a large, collapsed skylight

sitting in a chair is an old woman, her name is Thérèse Rivière, where are we? she asks. In a mental hospital, she answers. She accepts without concern the behavior of this traveler who comes and goes, exists, speaks, smiles at her, is silent, listens to her and disappears the sand on the floor changes and throbs as if the museum were the archive of her memory, the memories of a French ethnologist. We are in the Aurés, an extension of the Atlas Mountains in a colonial state called Algeria, the place where historically the Berbers resisted against the Romans, Vandals, Byzantines and Arabs. There are photos in the museum of unveiled Berber women, taken by a French army officer of his prisoners in 1960, one looks like Thérèse. As she looks up at the skylight, a Maqam Sigah (from Persian se-gāh سه + گاه = سهگاه "third place") widely used by Middle Eastern Jews for their cantilenas (Hebrew: טעמים) plays. Thérèse looks down, looks at the visitor, and says, "Let the waters be gathered into one place" (Book of Genesis 1:9)._

_Over the Maqam, a chant is superimposed. A sharp rhythm that pulls it upward like a human castle, a secularized religious tower along the peninsular Levant. Beyond the dome of the museum he sees the mosque of Jezzar Pasha (Arabic: جامع جزار باشا) erected by Ahmad Pasha el-Jazzar, famed for defeating Napoleon, and made of stones from other cities. He begins to hum a song in a language unknown to him. His feet rise on waves of sand, he remembers, his name is Abdellatif, and the language is Tarifit, that of his mother, Amazigh (in Berber language ⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖ)) from the Riff Mountains. Under the roof of the museum feels like far away, in Jerusalem in 1967, Sebag Yehuda, recorded by a Bengali man, plays the lute and sings in memory of Andalusia

through the skylight he goes out into the desert, leaving the museum under the dune. Already up, he observes how objects and instruments of all kinds are scattered on the dune, an accident of memories. With a sharp drop in bass frequencies he feels his hands begin to grind on the Mehbash, the coffee mortar of the Bedouins of Syria. A continuous, accelerated pulse entangles with new bass frequencies of the Sintir of the sub-Saharan slaves, mutually applauding each other and adding to the vibrations of the wax cylinder in the subsoil of the dune. Soil liquefaction begins to occur. The desert begins to take on the consistency of a heavy liquid. To the rhythm of the Mehbash, the desert engulfs and welcomes, with the irreversible hospitality of time, everything that previously floated on the sand. The museum scrambles to disappear along with hundreds of folded pipes of the organ of the cathedral of Seville with a jumble of frequencies and tones. As he whirls with the sand like a whirling dervish, he distinguishes among the distant polyphonies a few words: "I am not Christian, nor Jew, nor magician, nor Muslim. I am not of the East, nor of the West, nor of the land, nor of the sea." _

the desert engulfs him and he returns to the subsoil of the present._ continue reading...

Here you can see in detail the collage and the songs used in the piece with their albums/files of provenance:

album - Musique Traditionnelle Turque

artist - Ulvi Erguner, Akagündüz Kutbay and Dogan Ergin

place - Turquía, 1971

album - Mission Algérie-Aurès, 1936, Thérèse Rivière

artist - Arbia Bourzini

place - Aurés, 1936

This is the Ouled Abderrahmane tribe and it is a woman's song.

album - Syria - Musical Atlas - Unesco Collection

artist - The Rabitat al Mounshidin ensemble

place - Damasco, 1973

Maqam Sigah. This is an example of the sacred muwashshah which can be performed either in the mosque or elsewhere in particular circumstances. The text is an entreaty addressed to Allah the Merciful, who is our eternal hope.

album - Religious Music from the Holy Land

artist - VA

place - Palestina, 1968

Recorded in el Jezzar mosque during the annual gathering at the Id prayers on 8 July. Like an inmense choir but without a leader, the congregation of over four hundred people prayed and bowed, cried for God and paused in silence.

album - Turkish Village Music

artist - Bekir Tekbaş (Baglama [Saz])

place - Turquía, 1972

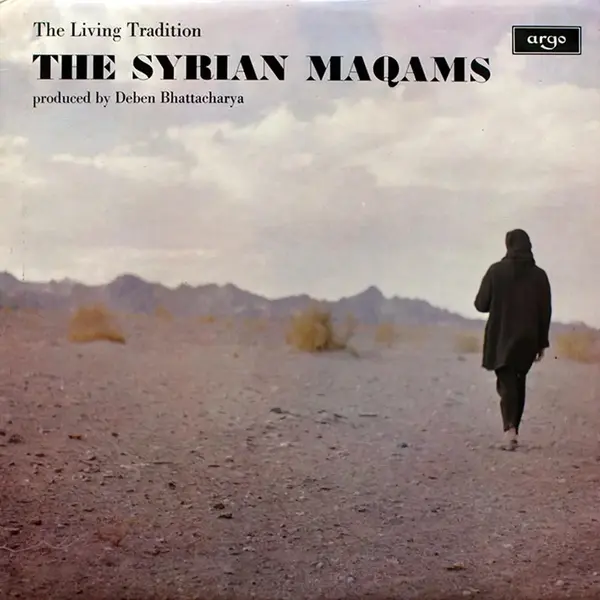

album - The Syrian Maqams

artist - Muhammad Abdul Karim

place - Siria, 1960

album - Fes IV 9/67 Alan Lomax

artist - Abdellatif ar-Riffi

place - Fez, 1967

Audio notes (Lomax) - A song taught to Abdellatif ar-Riffi by his mother, sung in Tarifit, the language of the Imazighen (Berbers) of the Rif Mountains. Riffi is an 18 year old engineering student who lives precariously in the medina -from region de Nadore.

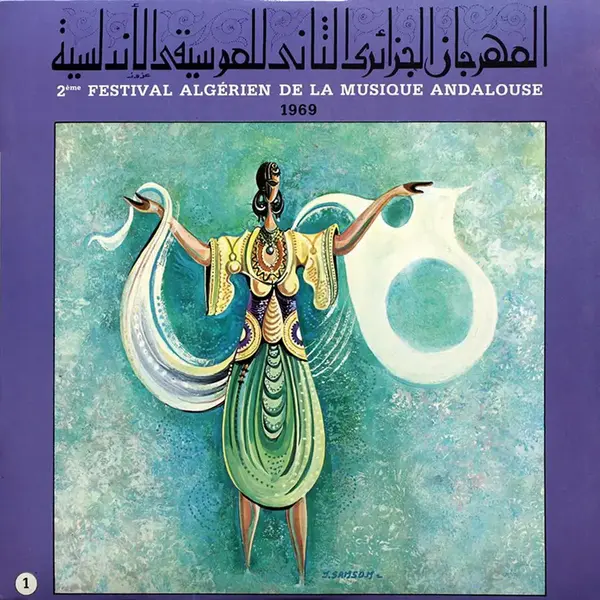

album - 2éme Festival Algérien de la Musique Andalouse 1969 disque 1

artist - Orchestre National de Radio Libye

place - Argelia, 1969

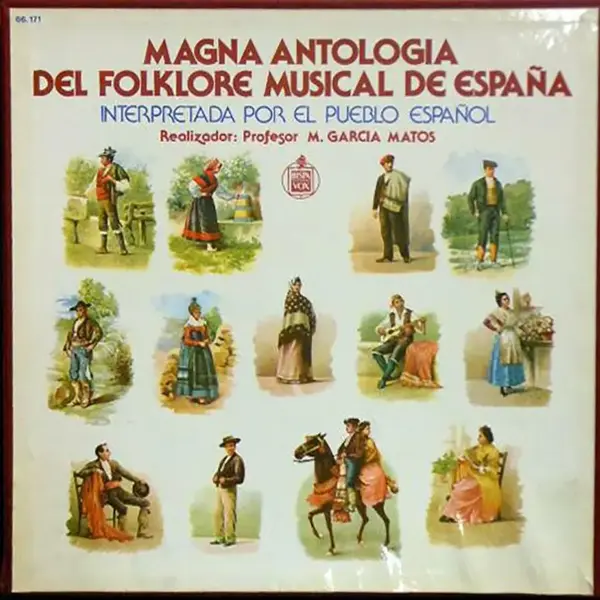

album - volume 05 - Catalonia - Aragon. Magna Antologia del Folklore Español

artist - VA

place - Tarragona, 1978

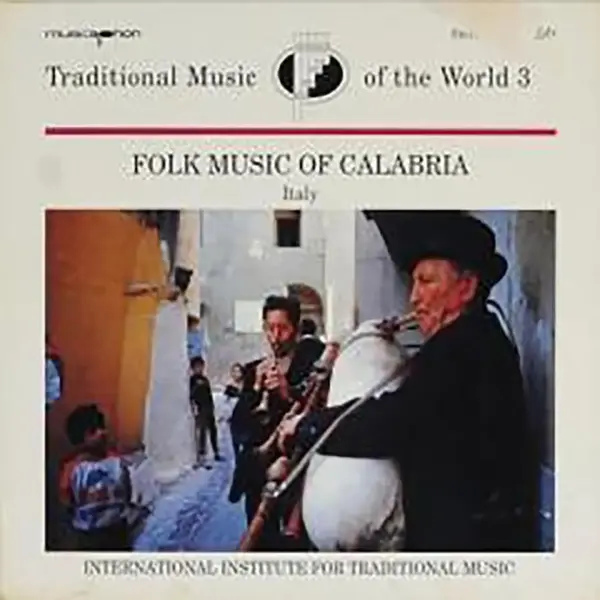

album - Folk music of Calabria

artist - VA

place - Italia, 1991

album - Maroc, Marrakech; Musique de confrérie

artist - Brotherhood of former black slaves Gnawa-Derbists, Bambara.

place - Marruecos, 1966

album - Music from the Middle East

artist - VA

place - Siria, 1967

Coffe in a Bedouin camp. The grinding of the beans is done with a wooden mortar and pestle. As the coffee is pounded, the up and down movement of the pestle produces the lower notes, and its sidewise movemet against the rim of the mortar produces the higher and ornamental beats.

album - Music from the Middle East

artist - Sebag Yehuda

place - Jerusalem, 1967

Notes from Deben Bhattacharya - Arabic love song in memory of Andalusia. While singing this love song, the singer accompanies himself on the 'Ud.

album - volume 08 - Balearic Islands - Basque Country. Magna Antología del Folklore Español

artist - VA

place - Baleares, 1978

album - Music of the Nile Valley

artist - Gamal Tewfick

place - Egipto, 1981

The Egyptian 'rababa' is composed of a resonator made of a coconut shell with a fish skin and mounted on a long tubular handle that is prolonged by an iron spike. two horse hair strings are vibrated by a large bow also strung with hair.

album - Middle East - Qanun Songs

artist - Elie Achkar

place - Líbano, 1996

album - Music Of Sardinia Vol. 3 - Traditional Songs & Dances Of Sardinia - Albatros VPA 8152

artist - VA

place - Cerdeña, 1967

Reed flute, triangle, Tambourine / Maracalagonis (Cagliari)

album - Sevilla / Alan lomax cultural equity

artist - E.G. León

place - Sevilla, 1952

Field log - 'an all night juerga [drinking bout and song fest] in Bar Luis down near the market in Seville. The singer and guitar player were paid for the evening by a wealthy man, Manuel León (Pepe la Triana) who invited me to come with my machine. The guitar player, El Rubio, Juan Antonio Martín, is the contact? the singer was a Gypsy named José Chamorro Pérez.' After the all-night session, around 8 -00 a.m., Lomax recorded several street vendors' cries.

album - Per Agata

artist - Donnisulana

place - Córcega, 1992

album - Sevilla / Alan lomax cultural equity

artist - Manuel Jiménez

place - Sevilla, 1952

Recorded in the Capilla Real of the Cathedral of Seville, by the organist Don Manuel Jiménez, Plaza de Santa Isabel 1. He plays dances and popular airs in the intervals between sections of the Mass.' One choral piece is sung by young female members of the Sección Femenina de la Falange Española

album - Por Derecho

artist - El Agujetas

place - Jerez de la Frontera, 1975

album - Al-Qahirah - Classical Music of Cairo

artist - Hesham El Araby

place - El Cairo, 1998

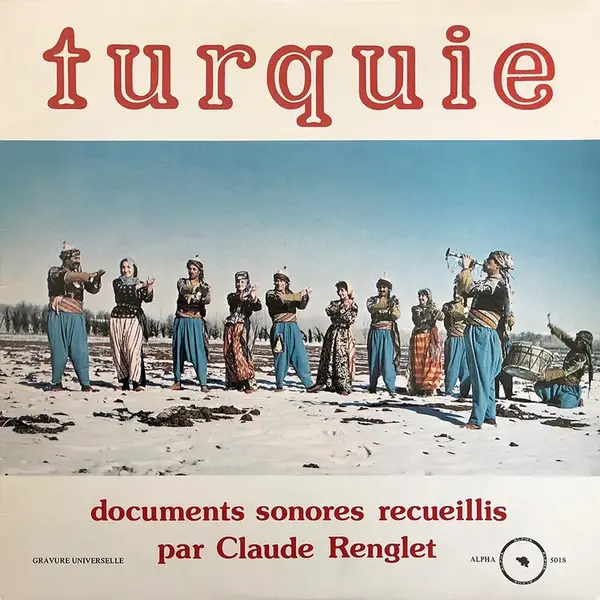

album - Musique de Turquie

artist - Order of the Whirling Derviches

place - Turkey, 1974

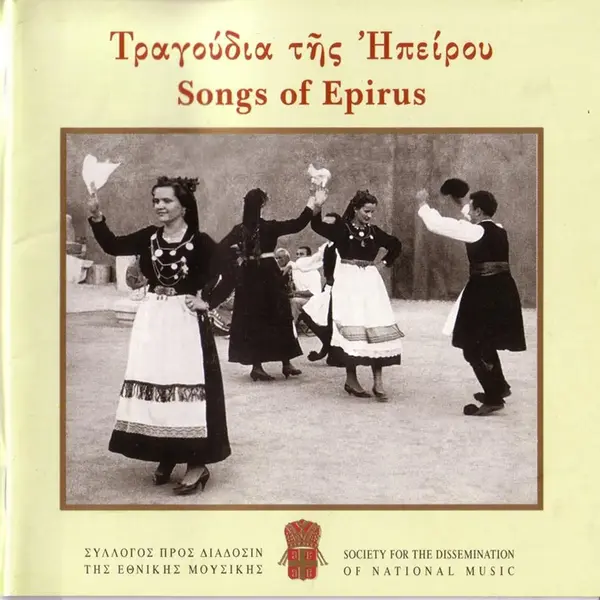

album - Songs of Epirus

artist - VA

place - Grecia, 1975

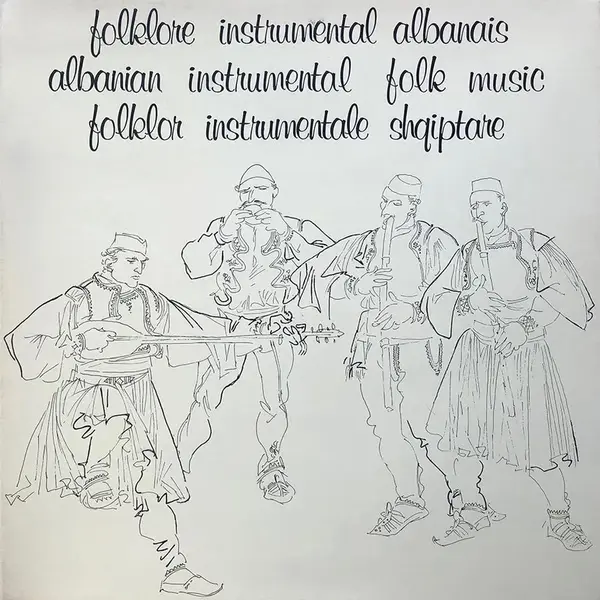

album - Albanian Folk Music - Disques Vendémiaire - VDE/PAL 114

artist - VA

place - Albania, 1981

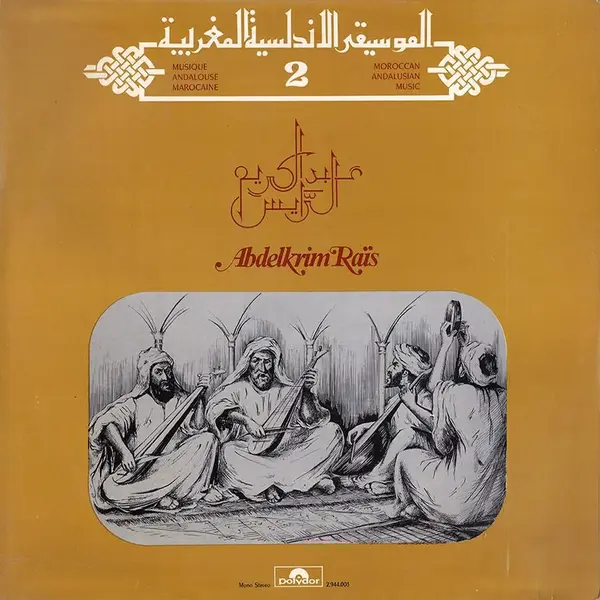

album - Abdelkrim Rais - Vol. 1

artist - Abdelkrim Rais

place - Marruecos, 1973